1 Considering that many older adults have atypical symptoms of delirium, a family member’s complaint that a patient is “not him/herself” should never be taken lightly.Efforts to educate the public about the prevalence of delirium and its risk factors for older adults will also help to address the under-recognition of delirium and its mismanagement in the clinical setting.AEIOU-TIPS is a mnemonic acronym used by many medical professionals to recall the possible causes for altered mental status, and there are many versions. Staff should also educate family members and caregivers to identify symptoms of delirium that warrant intervention by the interprofessional team.

This knowledge is essential to prevent and manage abrupt change in mental status in older adults. In all health care systems, providers and nurses would benefit from staff training by geriatric psychiatrists and specialists to recognize and differentiate symptoms of delirium from dementia. 3 Consultation with geriatric psychiatrists and pharmacists will be useful in determining appropriate interventions for these patients such as administration of haloperidol for severe agitation. 1 Pharmacological interventions should be used only in severely agitated patients at risk of self-harm or those with distressing psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. 3 Nurses may be assigned to work with agitated patients with delirium on a one-to-one basis to maintain safety and reduce need for physical restraints. It is important that patients have access to all sensory assistive devices, such as glasses, hearing aids, and dentures, to improve sensation and perception and reduce risk of disorientation and agitation. Providers should refrain from placing patients with delirium on bedrest and instead encourage mobility and patient involvement in self-care activities.

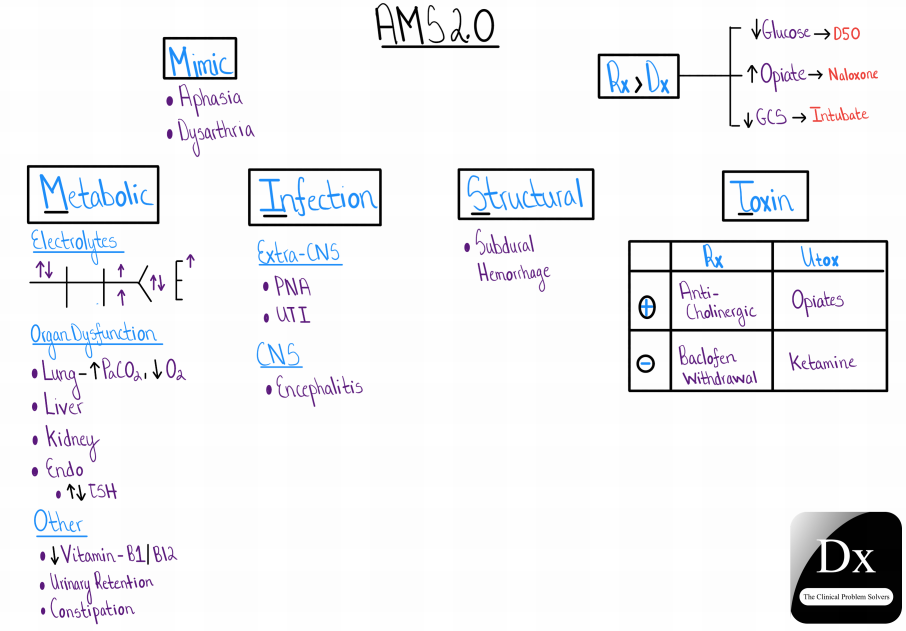

Family member and companion involvement in reorienting and comforting patient is also helpful. Non-pharmacological approaches to managing anxiety and promoting sleep and relaxation, such as massage, music, and warm beverages, are encouraged. 3 If patient has been taking anticholinergic and psychoactive drugs, providers and pharmacists should consider whether these medications can be reduced or discontinued. 1 The most important action for the management of delirium is identifying and treating the underlying cause of symptoms, such as dehydration, hypoxemia, and hypoglycemia. 4įor patients presenting with abrupt change in mental status on admission, family members can provide essential information about the onset and course of symptoms as part of the patient’s history to help providers distinguish between delirium and dementia. 1,2,3 Consultation with neurologists will also be important to rule out cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack as precipitating factors of abrupt change in mental status. A geriatric psychiatry consult may be ordered to assess appropriateness of prescriptions and adjust medications to keep use of sedatives and tranquilizers to a minimum. Medications should be reviewed every 24 hours by nurses, providers, and pharmacists to ensure they are appropriate for patient’s condition. Nurses can regularly reorient the patient to his or her environment and ensure adequate sensory stimulation to prevent confusion. 2 For patients identified at high risk for delirium, health care providers and nurses are encouraged to incorporate non-pharmacological prevention strategies into the plan of care. 1,3 Many cases of delirium develop during a patient’s stay upon exposure to risk factors such as infection, drug intoxication, and unfamiliar environment. Cognitive screening using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and other instruments are recommended for all older patients admitted to the hospital. Current evidence-based guidelines focus on prevention, recognition, and management of delirium in the complex older adult.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)